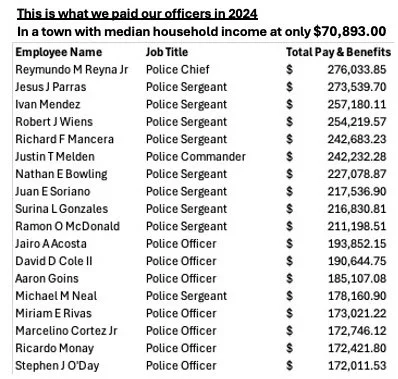

Compensation & Loyalty

At the Los Banos Police Department, officer compensation reflects not performance, but loyalty to the owners. Our salaries are generously overinflated, padded with overtime, bonuses, and benefits packages that would make actual public servants blush. This is not a mistake—it’s an investment.

We understand who we truly serve: city officials, political allies, donors, developers, and sponsors who expect discretion, protection, and unwavering loyalty. In return, our officers are rewarded handsomely for knowing when to enforce the law, when to ignore it, and when to stand quietly between power and consequence. Overinflated pay ensures silence, obedience, and the continued alignment of interests between the department and those who fund campaigns rather than communities.

Public justification for these wages often includes words like “danger,” “sacrifice,” and “heroism,” though most of the real work involves waiting, watching, and responding selectively. The result is a force that is not accountable to the public, but comfortably compensated to remain useful to the people who matter most. In Los Banos, service isn’t to the city—it’s to the sponsors who own it.

There is effectively no ceiling on compensation in Los Banos Police Department, only creative approach towards it. Salaries expand through overtime stacking, specialty pay, hazard bonuses for hazards never encountered, and end-of-career pay spikes designed specifically to inflate pension calculations. The arrangement doesn’t end when an officer leaves the force—it metastasizes. Taxpayers remain indefinitely responsible for lifetime pensions that outlast usefulness, oversight, or memory of service, often paying for decades after an officer has stopped pretending to work. Even misconduct rarely interrupts the flow. Resignation simply triggers the next phase of guaranteed income. In this system, public money isn’t spent—it’s locked in, ensuring that loyalty purchased during active duty is rewarded long after accountability would have been convenient.

Overcompensation as Control

In Los Banos, police salaries routinely reach three to four times the city’s median household income—not because the job is uniquely effective, dangerous, or successful, but because the compensation serves a very specific purpose: compliance.

High pay is not a reward for excellence; it is leverage. When an officer’s mortgage, lifestyle, pension, and social standing depend on the continued approval of city leadership and wealthy patrons, independence becomes an unaffordable luxury. Overcompensation ensures loyalty not to law, ethics, or community, but to the narrow class of people who influence budgets, contracts, and political survival.

Publicly, these wages are justified with carefully recycled language about sacrifice and risk. Privately, everyone understands the arrangement. Officers are paid well so they don’t ask questions, don’t push back, and don’t mistake their role as public servants rather than privately retained muscle with municipal branding. A paycheck large enough to separate them economically from the majority of residents ensures emotional and social separation as well.

The result is a force that no longer lives among the people it polices, cannot relate to the consequences of its actions, and has every incentive to protect wealth over wellbeing. When salaries place officers firmly above the communities they patrol, enforcement stops being about safety and starts being about order—specifically, the order preferred by those who can afford it.

In Los Banos, inflated wages don’t buy better policing. They buy silence, obedience, and reliability. And from the perspective of the city’s most powerful residents, that’s money very well spent.

Payroll is not the only thing that enriches our officers

We believe wealth should trickle upward—one officer at a time. At the Los Banos Police Department, we ensure financial security through overinflated salaries, endless overtime, and creative interpretations of “evidence handling,” where unlogged cash has a habit of finding new homes. Informal revenue streams flourish through a culture that looks the other way: kickbacks from drug distribution networks we allegedly “failed” to dismantle, partnerships with criminal enterprises that somehow never make it into reports, and suspiciously well-timed life insurance payouts following deaths we quickly classify as suicides before asking inconvenient questions. It’s not corruption if everyone involved is wearing a badge—or so the paperwork says. By the time an officer retires, they’re not just protected by a pension, but by a long trail of sealed records and people too afraid, poor, or dead to object.

Taxpayer money is the lifeblood of our department, and we take great care to spend it on literally anything except solving crimes. Public funds are routinely redirected toward baseball games, photo ops where we bribe children with toys to manufacture goodwill, and on-duty concierge services for wealthy residents who need escorts, favors, or problems quietly made to disappear. Actual crime fighting is inefficient and dangerous—worse, it’s bad for business. If crimes were solved, fear would drop; if fear dropped, budgets might shrink. So instead, we invest in visibility over results, optics over outcomes, and endless “community engagement” events that look productive while accomplishing nothing. After all, an unsolved problem is a renewable resource, and nothing justifies increased funding quite like failure wrapped in patriotism.